I felt so honored to be at the premiere of Vaclav Havel’s latest play, Odchazeni (Leaving.) Kate Connolly, a Guardian journalist, went around with a mic reminding everyone that it had been twenty years, since he had written a play!

I felt so honored to be at the premiere of Vaclav Havel’s latest play, Odchazeni (Leaving.) Kate Connolly, a Guardian journalist, went around with a mic reminding everyone that it had been twenty years, since he had written a play!

I must say, it was typicially Havel. He keeps his style of playing absurdism in a realistic setting, and I had to giggle at all of the conventions that I know so well from his earlier plays… the characters who appear on stage and don’t speak, but non the less steal the show, the hubris of the main character… yet it’s all in a post market economy context.

Havel says it’s not about him, but it’s about an ex Prime Minister, with a glamourous “long term girlfriend” (which his wife Dasa was meant to play), and his nemesis is a character called Klein (which couldn’t have anything to do with Vaclav Klaus.) The fact that his wife, actress Dasa Havlova, backed out of playing the role of Irena at the eleventh hour, was the subject of much gossip. Ostensibly her absence was for medical reasons, yet no one seemed to believe it… speculating that she had fought with her husband, or with Jan Triska (the lead actor) or the director. Yet, when I talked to other actors in the cast, it seemed that she really had simply stressed out, putting real pressure on a weak heart and thyroid. In any case, she was sitting next to him and smiling during the performance. (It must be stressful to play yourself in your husband’s play.)

As I was reading the play, previous to seeing it, I was snickering a lot about the convention of the “voice” which intermittently comments on the action, reminding the actors to stop exaggerating and over- acting, and occasionally criticizing the play’s construction. It turned out to be Havel’s voice, which was perfect. I noticed that one critic called this a “new convention,” but it reminded me of the voice from the hole in the wall in “Memorandum.” My friend Lou Charbonneau, who has done considerable research on the play, as he wrote his Master’s Thesis on it, told me that apparently Tom Stoppard advised him to loose the voice. At the end of the play, the voice enters to say something like “my colleague told me I should end the play here, but I must apologize to my advisor.” It must have been Stoppard. I’m glad he didn’t listen. As much as I like Stoppard, Havel has is own humble style that works for him. Part of that style, is doubting his every step, but then making fun of himself in the process.

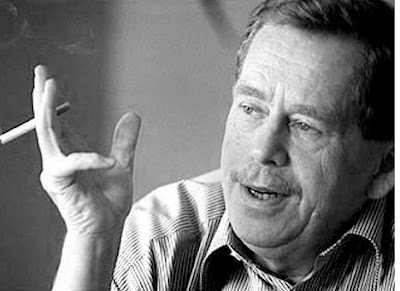

Martin Palous (Czech ambassador to US) introduced me to Havel in glowing terms, saying “this is Nancy Bishop who directed a very funny film about Americans living in Prague,” and I shook his hand, but it was awkward and I didn’t know what to say to him beyond congratulations. My first meeting with him was much more interesting. It was a summer night in the year 1995. President Havel was enjoying a beer at a pub on the stairs to the castle. He was sitting with Dasa though it was before their marriage. I introduced myself in my awkward novice Czech and told him that I was directing one of his plays in English (I think it was Protest.) I then told him that it seemed that many Czechs didn’t like it that Americans were working on his plays in Prague. He smiled at me and said, “before the revolution there were 10 million Czech communists, but now after the revolution there are 10 million Czechs against communism.”